For decades, scientists have wrestled with a stubborn paradox. Humans depend on cooperation, yet we repeatedly overdraw shared resources. Fisheries collapse. Antibiotics lose their punch. Carbon fills the atmosphere. The logic is familiar: short-term individual gains overpower long-term collective good.

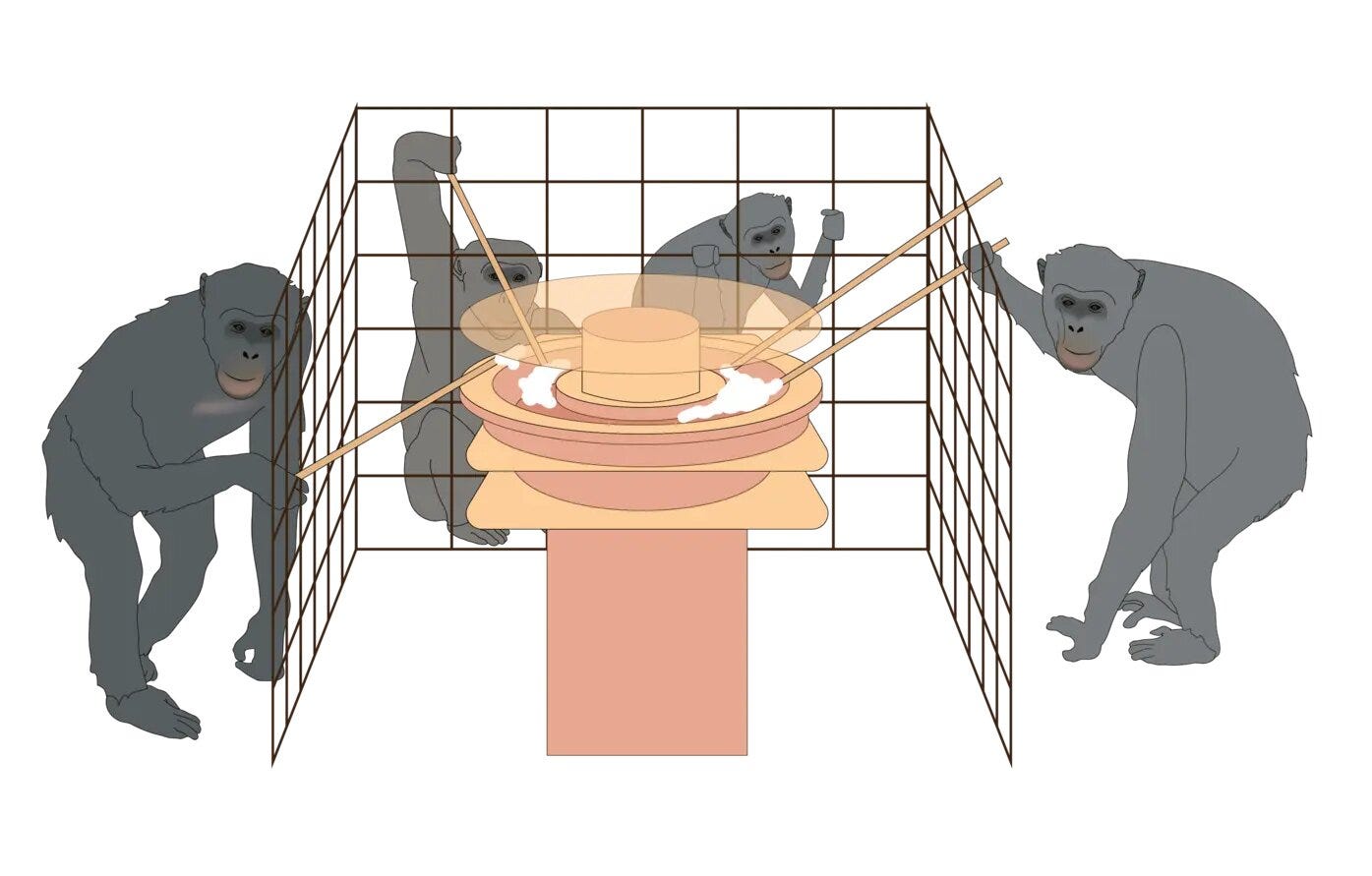

Now a carefully designed experiment with chimpanzees suggests that some of the ingredients for sustainable cooperation predate Homo sapiens. In a new study1 from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and collaborators, chimpanzee groups faced a classic “common-pool resource” dilemma. The results point to an unexpected lesson. Bigger groups, when socially tolerant and guided by restrained leaders, outperformed smaller ones at keeping a shared resource available.

The findings offer a window into the social roots of cooperation and hint that some of the failures seen in human societies may not stem from group size alone, but from how power and tolerance are distributed within them.