There is something genuinely strange about the way bonobos use sex. Not strange in the tabloid sense, though that framing has followed these apes around since they were popularized in the 1990s. Strange in the evolutionary sense: Pan paniscus deploys sexual behavior as a kind of social Swiss Army knife, using it to resolve conflict, build alliances, and manage the complex politics of a matriarchal society. Sex is not just reproduction for bonobos. It’s communication.

Which raises a question that a team of researchers from Italy, Belgium, and beyond decided to take seriously: if sex is communicative, what exactly is being communicated, and how?

The study, led by Martina Francesconi and Elisabetta Palagi at the University of Pisa and published in Evolution and Human Behavior,1 didn’t approach this from the angle you might expect. They weren’t primarily interested in who was having sex with whom, or under what social circumstances. They were interested in tempo. Specifically, the rhythm of repetitive movement during sexual activity, and what happens to that rhythm when facial expressions enter the picture.

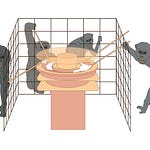

The data came from detailed video recordings of bonobos in zoo settings, analyzed frame by frame. The precision matters here. You can’t eyeball rhythm. What looks like a steady pace to a human observer may contain real variation that only shows up when you quantify it. Yannick Jadoul, a data scientist at VUB whose contribution to the study was the quantification of that rhythm, was careful to note that this is rigorous pattern recognition, not the kind of AI most people picture. It’s systematic measurement of complex behavior, applied to a domain where impressionistic observation has limits.

What they found: the tempo of movement during bonobo sexual activity runs high, averaging around seven movements per second. That’s fast. And it tends to stay fast, which is interesting in itself.