Picture this: a 43-year-old bonobo watches as a researcher tips an empty pitcher over two empty cups, miming the gesture of pouring. The researcher then “empties” one of the cups back into the pitcher. When asked where the juice is, the bonobo points to the correct cup. The one that still contains the imaginary liquid.

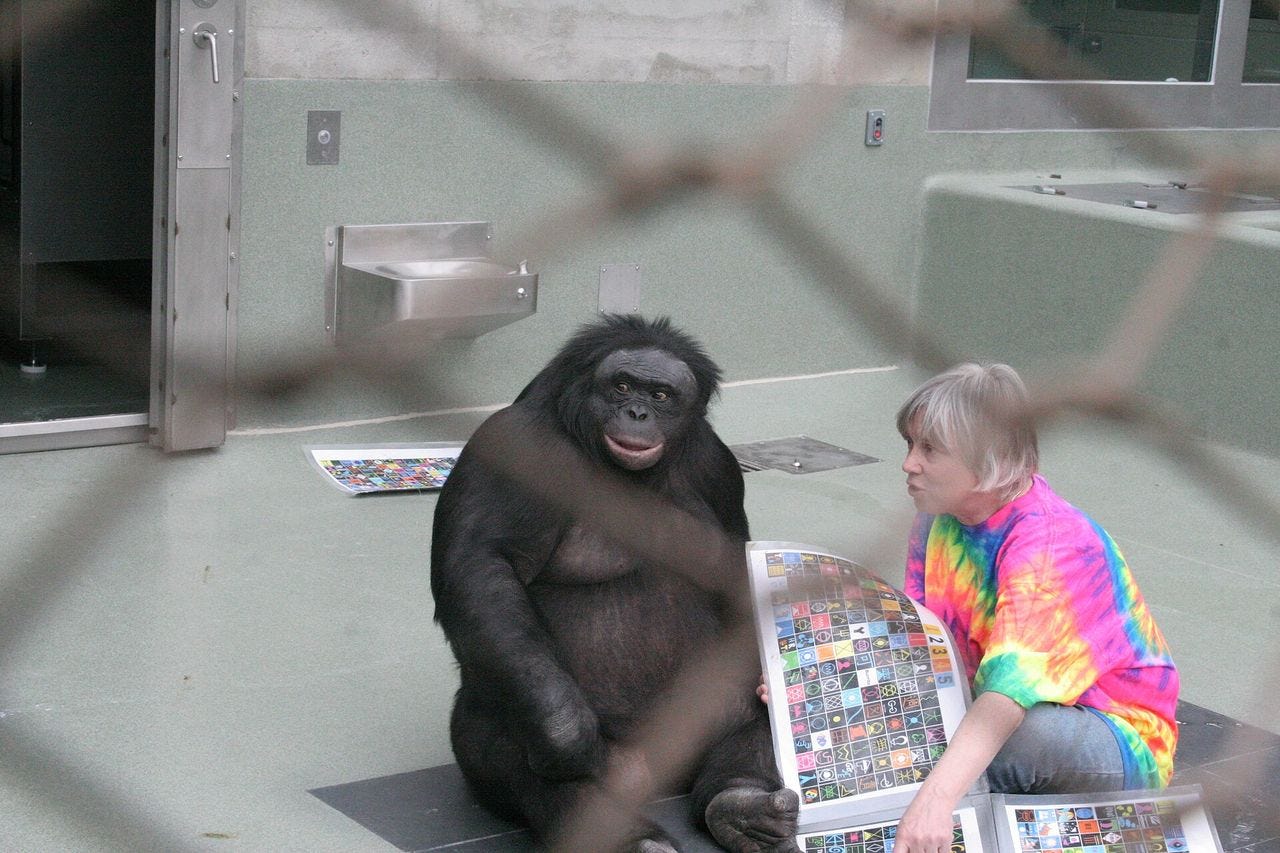

This is not a party trick. Kanzi, a lexigram-trained bonobo living at a research facility, has done something that forces a rethinking of what cognitive abilities existed in the common ancestor we share with other great apes. In a study published in Science1 in February 2026, researchers Amalia Bastos and Christopher Krupenye documented Kanzi’s ability to represent pretend objects across three separate experimental paradigms. He tracked imaginary juice. He distinguished real grapes from pretend ones. He kept straight what was there and what was only supposed to be there.

The implications ripple outward. If a bonobo can do this, the capacity for what cognitive scientists call secondary representation likely existed in the last common ancestor of humans, chimpanzees, and bonobos, an animal that lived somewhere between six and nine million years ago.