When a friend leaves the room, they don’t vanish from awareness. The mind holds their presence in place, tethered invisibly to a mental map of who is where. For humans, this ability is so intuitive that it rarely receives attention. Yet whether other primates share this capacity has long been debated.

A new study led by researchers at Johns Hopkins University suggests that at least one bonobo, named Kanzi, can do just that. The findings show that bonobos can mentally track the locations of multiple individuals at once, even when those individuals are hidden. The results add another piece to the puzzle of how social cognition evolved in apes and humans alike.

“People think social intelligence is a thing that makes humans unique—that, because we have to manage so many different relationships, we might have a range of cognitive tools for doing so that will only be found in ultra-social species like humans,” said Chris Krupenye, senior author of the study.

“But most of us who study apes have a strong intuition that, because the social world is so important for them too, they must, like humans, be keeping track of these critical social partners.”

The study, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B1, combined classic hide-and-seek games with photographs and voices of Kanzi’s caregivers. The results indicate that bonobos not only remember who individuals are, but also where they are—even when they cannot be seen.

Hide and Seek in the Bonobo Mind

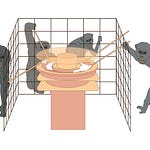

Kanzi, a well-known research bonobo, was tested in a series of trials. Two familiar caregivers hid behind barriers while an experimenter presented Kanzi with photographs. He was then asked to indicate where each person was concealed.

A series of hide-and-seek experiments with a bonobo named Kanzi shows for the first time that apes can mentally keep track of multiple familiar humans at once, even when they are out of sight. Kanzi could also recognize caregivers from their voices alone, an ability never before tested on bonobos. Credit: Johns Hopkins University

Kanzi performed well above chance. Even when the experiment shifted to auditory cues—where he could only hear caregivers’ voices from behind the barriers—he still successfully matched voice to face and location.

“He does have the capacity to use voice as a marker for identity. This face matches this voice,” said lead author Luz Carvajal.

Across the experiments, Kanzi demonstrated what psychologists call “integrated memory.” He was not only recalling voices and faces, but also mapping them to spatial locations, showing that his memory could bind together multiple pieces of information about social partners.

Why Tracking Minds Matters

For bonobos and chimpanzees living in the dense forests of Central Africa, groupmates disappear and reappear throughout the day. Knowing where allies, rivals, or kin are located—even when they are out of view—could shape everything from foraging success to social alliances.

The ability to mentally represent absent group members may therefore not be uniquely human. Instead, it may be part of a shared inheritance within the great apes.

“Across these studies the results suggest that Kanzi has a memory of these individuals that brings together their vocal and visual identities—who they are and what they sound like, and where they are in space,” Krupenye explained.

The researchers now plan to test how many individuals bonobos can track at once, and how long these memories persist.

The Bigger Picture: Social Minds Before Homo

These findings matter for anthropology as much as for primatology. Social tracking has long been considered one of the foundations of human intelligence. The capacity to mentally juggle the whereabouts of kin and allies likely helped early hominins manage increasingly large and complex social groups.

If bonobos share this skill, then the evolutionary roots of social tracking stretch back before the divergence of humans and bonobos, roughly 6 million years ago. That makes it less a uniquely human innovation and more a deep ancestral trait.

“These animals are rich and complex,” Krupenye said. “Even if we just want to understand ourselves better, there’s an urgency to this work and to saving this endangered species.”

This study builds on a growing body of evidence about ape social cognition:

Chimpanzees can recognize groupmates’ faces and calls even after years apart (Parr et al., 2000).

Fieldwork suggests apes remember the outcomes of past cooperative hunts and alliances (Boesch & Boesch-Achermann, 2000).

Great apes demonstrate episodic-like memory, recalling “what, where, and when” events occurred (Martin-Ordas et al., 2010).

Together, these findings challenge the idea that mental tracking of absent individuals is unique to humans. Instead, they suggest that the roots of social intelligence lie deeper in our shared evolutionary past.

Related Studies

Parr, L. A., Winslow, J. T., Hopkins, W. D., & de Waal, F. B. (2000). Recognizing facial cues: Individual recognition in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Animal Behaviour, 59(4), 845–855. https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1999.1415

boesch, C., & Boesch-Achermann, H. (2000). The Chimpanzees of the Taï Forest: Behavioural Ecology and Evolution. Oxford University Press.

Martin-Ordas, G., Call, J., & Colmenares, F. (2010). Memory for distant past events in chimpanzees and orangutans. Current Biology, 20(12), R557–R558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.047

Carvajal, L., & Krupenye, C. (2025). Mental representation of the locations and identities of multiple hidden agents or objects by a bonobo. Proceedings. Biological Sciences, 292(2053). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2025.0640