On Jicarón Island, a dense tangle of rainforest off Panama’s Pacific coast, a small band of white-faced capuchin monkeys (Cebus capucinus imitator) has developed a disturbing social practice: abducting and carrying the infants of another primate species1. These are not acts of predation. Nor do they resemble maternal behavior. Instead, they occupy a liminal space between play, curiosity, and something more troubling.

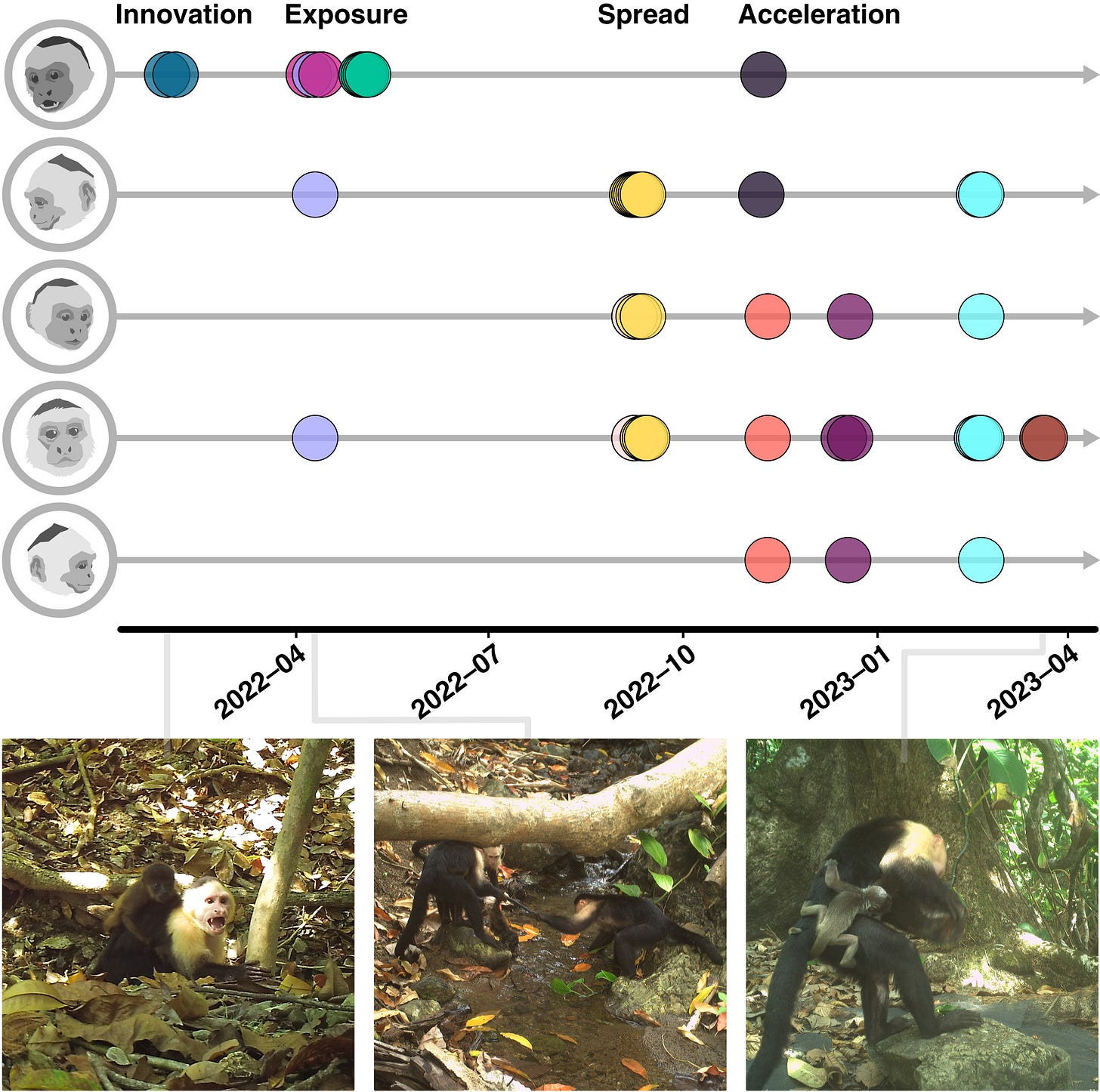

Between January 2022 and July 2023, researchers documented 11 such incidents. All involved young male capuchins and infant howler monkeys (Alouatta coibensis), a species known more for its rumbling vocalizations than for agile evasion. The pattern began with one capuchin, dubbed Joker, and spread to others, forming what scientists now describe as a nascent social tradition—possibly even a cultural innovation.

“Looking at the footage and not knowing what was going to happen was somewhat like watching a horror movie that was being written,” said primatologist Brendan Barrett, a co-author of the study published in Current Biology.

Borrowed Babies, No Return Policy

In camera footage, Joker is often seen cradling a howler infant like an accessory, moving through his daily routines with the infant latched to his chest or back. He doesn’t groom the infant. He doesn’t feed it. He simply carries it—until, in most cases, it dies. The researchers confirmed four deaths; the remaining outcomes are unknown but presumed fatal, given the infants’ separation from nursing mothers.

“He looked like a shopper carrying a chihuahua in her purse,” observed anthropologist Meg Crofoot. “But it wasn’t cute. It was grim.”

The abductions don’t appear motivated by aggression, yet they are not benign. In one clip, adult howlers vocalize in distress as a group of capuchins prevents an infant from returning to its troop. The behavior seems to occupy an ambiguous space in the moral universe of primates—neither clearly violent nor compassionately protective.

A Culture of Experimentation?

The capuchins of Jicarón are already known for their tool use. They use stones to crack mollusks and other hard-shelled prey, making them one of the few primates to independently develop such technology. The link between tool use and behavioral experimentation has not gone unnoticed.

“It may not be a coincidence that monkeys using tools are also inventing rituals,” noted Crofoot. “They may just have a lot of time on their hands.”

Jicarón and neighboring Coiba Island offer an unusual ecological setting: no natural predators, abundant resources, and few interspecies conflicts. These conditions may create a crucible for behavioral innovation—and, perhaps, misbehavior.

Charlotte Burn, a behavioral specialist unaffiliated with the study, cautioned against hasty anthropomorphism. Still, she acknowledged the need to explore whether boredom, isolation, or social status might be driving these behaviors. Was Joker a lonely subadult? Did abducting infants raise his profile within the group?

“Maybe they too are missing whatever he was missing,” Burn speculated.

Between Curiosity and Cruelty

Capuchins are known for complex social behaviors and, at times, for targeted aggression. Susan Perry, an anthropologist at UCLA, once documented them torturing coati pups and tossing baby kinkajous like toys. But the howler monkey abductions don’t fit that mold. They lack the overt cruelty of predation yet still cause harm.

This raises a deeper question: Are these capuchins inventing new social roles? Are they testing boundaries not just of behavior, but of empathy, responsibility, and social reward?

If such acts are cultural innovations—transmitted through observation and imitation—they suggest that the roots of human ritual, and even of transgressive behavior, may lie in a shared primate capacity for creativity. But in the absence of clear utility, morality, or even coherence, they also force us to reckon with the ambiguities of animal minds.

“It’s not violence in the way we think of it,” said Barrett. “But it’s also not caregiving. It’s something stranger—somewhere in between.”

Further Reading and Related Research

Perry, S. (2011). Social traditions and social learning in capuchin monkeys. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366(1567), 988–996. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0346

Fragaszy, D. M., & Perry, S. (2003). The Biology of Traditions: Models and Evidence. Cambridge University Press.

Haslam, M. et al. (2009). Primate archaeology. Nature, 460, 339–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08188

Leca, J.-B., Gunst, N., & Huffman, M. A. (2010). Differences in social tolerance and innovation in Japanese macaques and chimpanzees: Implications for the evolution of cultural intelligence. Primates, 51(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-009-0174-9

Goldsborough, Z., Crofoot, M. C., Jacobson, O. T., Corewyn, L., Rosario-Vargas, E. del, León, J., & Barrett, B. J. (2025). Rise and spread of a social tradition of interspecies abduction. Current Biology: CB, 35(10), R375–R376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2025.03.056