Climate Shock in a Biodiversity Stronghold

In March 2019, Cyclone Idai barreled into central Mozambique with winds topping 220 km/h and torrential rains that submerged entire communities. Among the hardest-hit places was Gorongosa National Park, a mosaic of floodplain, forest, and savanna that shelters a wide range of wildlife—including some of the country’s least-studied primates.

The cyclone's human toll was devastating. But its effects on wildlife, particularly primates, offered an unusual scientific opportunity. Using years of camera trap data, a team led by Megan Beardmore-Herd tracked how baboons and vervet monkeys in Gorongosa coped with—and rebounded from—an environmental jolt rarely recorded in such detail.

“With climate events like cyclones becoming more intense and less predictable, it’s crucial to understand how animals respond—not just in terms of survival, but in how they change their space use and behavior,” said Beardmore-Herd, whose study appears in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology1.

The Flood That Followed the Wind

Gorongosa is no stranger to seasonal flooding. Lake Urema—the park’s central water body—swells each rainy season. But the deluge that followed Cyclone Idai was different. Waters rose sharply and stayed high, pushing primates and other animals to adapt on the fly.

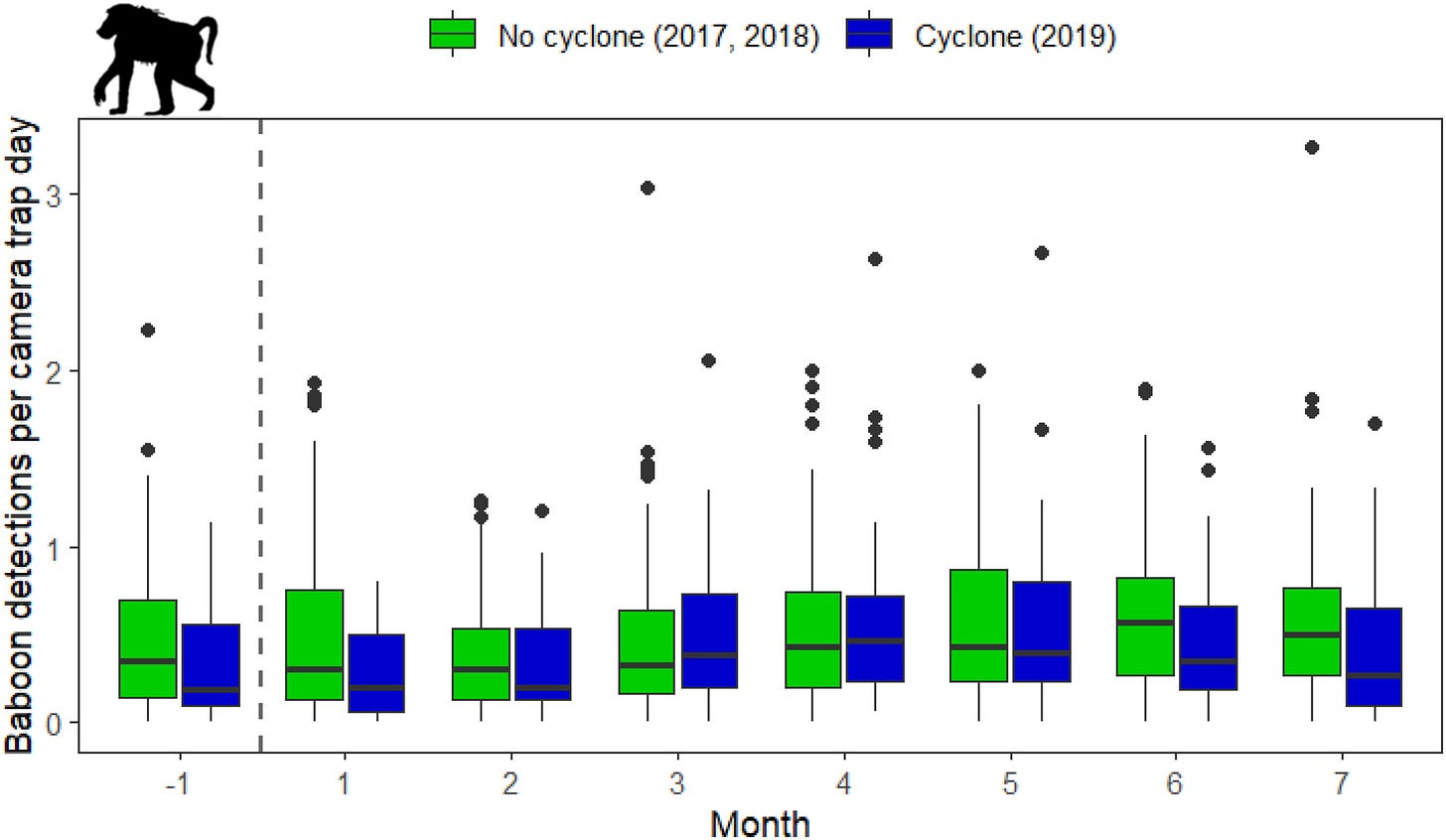

Camera traps stationed throughout the park captured this shift in near-real time. In the month after the cyclone, gray-footed chacma baboons (Papio ursinus griseipes) were detected less often near the lake and more often in upland zones spared the worst flooding.

“Baboons seemed to have moved away from the floodwaters immediately after the storm, then gradually returned to their usual ranges within two months,” the researchers observed.

The temporary relocation reflected behavioral flexibility, a trait often cited as a hallmark of primate adaptability—and, possibly, a key factor in hominin survival during past climatic swings.

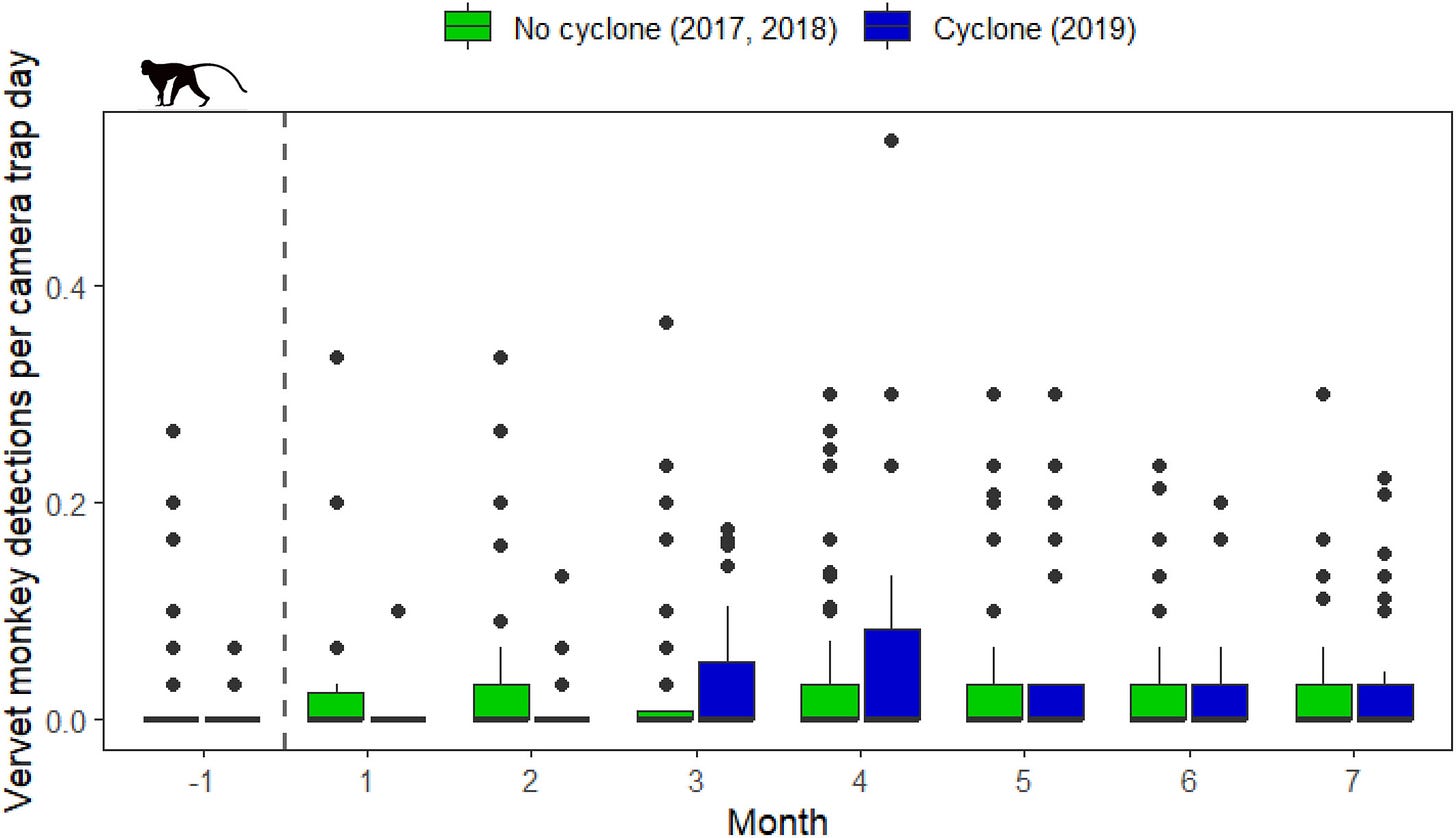

Vervet Monkeys and the Problem of Detection

Vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus pygerythrus), lighter and more arboreal than baboons, presented a more ambiguous picture. Detection rates for vervets were consistently lower—not necessarily because there were fewer monkeys, but because terrestrial camera traps are less suited for spotting creatures who spend much of their time in the canopy.

Still, some patterns emerged. In the first month post-Idai, vervet detections dropped. But by the fourth month, they had bounced back, even exceeding pre-cyclone levels in some areas.

“Their return suggests resilience,” said Beardmore-Herd. “But the data also highlight a methodological blind spot: to fully understand how arboreal primates respond to rapid environmental change, we need better tools—possibly a mix of canopy cameras and direct observation.”

Lessons for the Anthropocene—and the Pleistocene

The idea that primates are flexible, clever survivors is not new. What this study offers is a rare, quantified snapshot of those abilities in action, across a whole landscape, before and after a massive ecological shock.

“The findings suggest that behavioral adaptability—ranging shifts, diet flexibility, movement to higher ground—is not just a short-term coping mechanism. It may have played a central role in primate evolutionary history.”

This echoes ideas proposed by paleoanthropologist Rick Potts, whose “variability selection” hypothesis argues that early humans evolved key traits like tool use and social cooperation in response to fluctuating environments. Watching baboons and vervets improvise under pressure in modern Mozambique may provide a living analogue for how our ancestors navigated similarly chaotic landscapes during the Pleistocene.

Not All Species Weather the Storm Equally

Notably, the baboons and vervets in this study fared better than some of their herbivore neighbors. Earlier work by Walker and colleagues (2023) showed that small-bodied antelope species struggled during Idai, many unable to escape or find food in the flood’s wake.

That baboons—mid-sized at best—adjusted effectively may point to advantages beyond body mass. Their diet, social dynamics, and cognitive toolkit likely gave them a leg up.

“Traits like social learning and spatial memory could make a critical difference when every minute and meter of higher ground counts,” the study notes.

Still, caution is warranted. The camera data can’t distinguish between survivors and immigrants, nor can it capture births, deaths, or long-term stress. Infant and juvenile baboons did go missing in the immediate aftermath—losses that may signal reproductive costs down the line.

The Climate Future Is Already Here

This study is not just about one storm or one park. It points to a broader reality: primates are being asked to adapt faster than ever before. Climate change is not a future threat—it’s a lived one.

And yet, adaptability has limits. Not every primate has the cognitive or ecological breadth of a baboon. For more specialized species, or those confined to narrow habitats, an Idai-scale event could spell collapse.

“Understanding which species can bend and which might break is essential,” said Beardmore-Herd. “That knowledge should inform both conservation and our models of how climate shaped human evolution.”

Related Research

Pavelka, M. S. M., McGoogan, K. C., & Steffens, T. S. (2007). Primates and Hurricanes: A Review. American Journal of Primatology, 69(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20321

McFarland, R., Fuller, A., Hetem, R. S., Mitchell, D., Maloney, S. K., & Henzi, S. P. (2014). Social integration confers thermal benefits in a gregarious primate. Journal of Animal Ecology, 84(4), 871–878. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12308

Walker, R. H., Gaynor, K. M., Palmer, M. S., et al. (2023). Large herbivore responses to cyclone-induced flooding in Gorongosa. Ecology Letters, 26(9), 2050–2064. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14283

Zhang, S. Y., et al. (2019). Predicting the vulnerability of primates to climate change. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 28(2), 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12823

Beardmore-Herd, M., Palmer, M. S., Gaynor, K. M., & Carvalho, S. (2025). Effects of an extreme weather event on primate populations. American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 186(1). https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.25049