In a quiet corner of the Leipzig Zoo, a group of bonobos sat before trays of fruit. Some were given choice pieces—sweet grapes and ripe bananas. Others received only celery or nothing at all. Their reactions, subtle yet telling, are now helping scientists refine a long-standing question in anthropology: Do non-human primates have a sense of fairness?

A study published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B1 by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and Utrecht University suggests the answer may be yes—at least for bonobos. The findings shed new light on the evolutionary foundations of fairness, cooperation, and social bonds among our closest primate kin.

The Fairness Dilemma

The capacity to detect unfair treatment is a cornerstone of human morality. Children as young as two will protest when they receive less than their peers. But whether this behavior is uniquely human—or whether it has evolutionary precursors—is far from settled.

“Fairness is more than a cultural construct,” said lead author Kia Radovanović of Utrecht University. “It might be a social tool embedded deep in our primate lineage.”

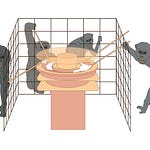

To test this, Radovanović and her colleagues observed six bonobos at the Wolfgang Köhler Primate Research Center. Each bonobo was asked to exchange a token for a food reward, but the catch was in the reward distribution. Sometimes both partners received the same treat; other times, one was shortchanged.

Refusal as Protest

What happened next was not just behavioral noise. When bonobos received a less-preferred item while their partner got something better, they often refused to continue the exchange. This wasn’t a matter of general frustration; researchers controlled for that by testing responses to unfulfilled expectations separately.

“We found that bonobos more often refused to participate when faced with inequitable rewards,”

said Radovanović.

“Their reactions weren’t simply due to disappointment with the experimenter, but reflected a genuine aversion to unequal treatment.”

This behavior stands in contrast to chimpanzees, who often accept unfairness if the outcome still yields a reward. For bonobos, inequity itself seemed to sour the deal.

Not All Inequity Is Equal

Importantly, the bonobos’ tolerance for inequality shifted depending on their social relationships. When paired with closely bonded partners, they were more willing to accept a lesser reward. This social nuance mirrors similar findings in human behavior, where perceived fairness often depends on context.

“Bonobos appear to make fairness judgments that are flexible and socially informed,” said Daniel Haun, director at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. “This suggests that inequity aversion may have evolved as a stabilizing force for cooperation among close social partners.”

The study’s controlled design strengthens its conclusions. By separating disappointment with the experimenter from inequity responses, the researchers clarify that bonobos weren’t just reacting to an unmet expectation—they were reacting to social unfairness.

Why Fairness Might Matter in Evolution

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) and chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) share about 98.7% of their DNA with humans, but their social strategies differ. While chimpanzees often rely on aggression and dominance hierarchies, bonobos lean toward affiliation, cooperation, and maternal influence.

In this context, fairness becomes more than a moral idea—it becomes a social currency.

“Recognizing and responding to inequity may promote long-term cooperative relationships,” Radovanović explained. “It encourages partners to treat each other equitably, maintaining social cohesion over time.”

The study adds to a growing body of research exploring the evolutionary origins of moral behavior. From capuchins throwing cucumbers in protest to elephants mourning their dead, the animal kingdom is revealing more complexity than once believed.

Next Steps in Primate Fairness Research

Still, the researchers caution that six bonobos are not enough to draw broad conclusions. The team plans to expand their sample size and explore how bonobos behave in more naturalistic cooperative contexts.

“This study provides new insights into how fairness may have evolved,”

said Haun.

“But testing larger groups and examining inequity aversion in real-life cooperation settings will be key.”

For anthropologists and evolutionary scientists, the study underscores how closely our ethical intuitions may be tied to our primate roots. Fairness, it seems, didn’t just arise in courtrooms or playgrounds—it may have emerged in the forests and social alliances of our earliest relatives.

Related Research

Brosnan, S. F., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2003). Monkeys reject unequal pay. Nature, 425(6955), 297–299.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01963Engelmann, J. M., & Tomasello, M. (2019). Children’s sense of fairness as equal respect. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(6), 454–463.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.03.001Massen, J. J., & Koski, S. E. (2014). Chimps cooperate, but not fairly: A nuanced view of fairness in nonhuman primates. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 221.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00221Boeckle, M., Schiestl, M., Frohnwieser, A., Gruber, R., & Bugnyar, T. (2020). Raven’s responses to inequity in feeding contexts. Animal Behaviour, 170, 109–121.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2020.01.007

Radovanović Kia, Lorskens Anoek, Schütte Sebastian, Bräuer Juliane, Call Josep, Haun Daniel B. M. and van Leeuwen Edwin J. C. 2025Bonobos respond aversively to unequal reward distributionsProc. R. Soc. B.29220242873 http://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2024.2873