For decades, recursion has been treated as a sort of linguistic fingerprint unique to humans. This is the idea that you can place a structure within a structure—like clauses within sentences, or folders within folders—to generate limitless meanings from limited parts. But new evidence1 from the Sumatran rainforest complicates this tidy distinction between human and animal communication. Orangutans, it turns out, may be speaking in rhythms that are mathematically and cognitively much closer to our own than once assumed.

Nested Calls in the Canopy

A team led by Dr. Chiara De Gregorio and colleagues Adriano Lameira and Marco Gamba has documented something never before seen in nonhuman primates: third-order self-embedded vocal motifs in wild Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii). These aren't just patterns of repetition—they’re deeply structured, recursive rhythms akin to how human language layers meaning.

"Recursive operations underpin great ape call combinatorics, operations that likely evolved gradually in the human lineage as vocal sequences became longer and more intricate," the authors note.

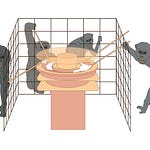

By studying alarm calls given by female orangutans when confronted with different types of predator models—including camouflaged humans made to resemble tigers—the researchers noticed the calls followed a tripartite structure:

Combinations: Individual calls grouped closely in time

Bouts: Combinations grouped into larger units with consistent intervals

Series: Bouts themselves grouped into even larger-scale sequences

Each level followed a consistent rhythmic structure—what scientists refer to as isochrony—meaning the timing between units was evenly spaced, like the ticking of a metronome.

Not Just Noise

This organization wasn’t arbitrary. The team observed that orangutans adjusted the tempo of their calls based on the perceived danger of the threat. When responding to a natural predator (a tiger), their calls sped up; when presented with a less credible threat (such as a patterned cloth), the rhythm slowed and lost regularity. In other words, these apes weren’t just making noise. They were encoding and modulating information through structured patterns.

"This could be the first empirical evidence that recursive vocal operations were likely present in ancient hominids across taxa and geography, likely deployed by males and females, and dynamically used to encode information," the study argues.

Echoes of Music and Syntax

To understand the power of what’s happening, it helps to think in musical terms. Many of us can recognize a melody that unfolds over several bars, with nested patterns repeating across different layers of time. Orangutan calls showed a similar structure, with recursion at three levels—[isochrony [isochrony [isochrony]]]. That’s recursion to the third power.

The time intervals are striking. Combinations had a tempo around 0.26 seconds. Bouts stretched out to about 1.1 seconds. Series? Over 8 seconds on average. This creates ratios of roughly 2:9:67 across layers—suggesting not only structural depth but a level of neural control not typically credited to nonhuman primates.

Why It Matters

Recursive vocal behavior has long been held as a kind of Rubicon separating human language from other forms of animal communication. That boundary is now looking more porous. The orangutan data follows earlier findings in male Bornean orangutans, where second-order recursion was observed. Taken together, these studies make it harder to argue that recursive capacity is a binary trait—either present or absent.

Instead, this research supports a model of language evolution as gradual and cumulative. The seeds of recursion may have existed long before Homo sapiens shaped them into grammar and syntax. Natural selection, acting on vocal rhythms that already conveyed social or environmental meaning, could have slowly favored ever-deeper levels of organization.

An Embodied Brain?

One tantalizing possibility is that recursion in vocalization might be an emergent property of brain architecture. Human and primate brains are themselves recursively structured, with nested layers of processing. The orangutan findings raise the prospect that certain thresholds of neural complexity might naturally yield recursive vocal output.

This would help explain why such a system hasn’t been observed in other animals—even those with sophisticated vocal abilities. Unlike birds or dolphins, great apes share with humans a deep evolutionary history of brain organization.

Broader Implications for Language Evolution

Much of the debate over the origins of language has been shaped by the assumption that recursion came late, suddenly, and fully formed—an idea famously advanced by Noam Chomsky and colleagues. These new data suggest otherwise. They align with an incremental model of language evolution, in which each layer of complexity builds on existing cognitive substrates.

They also open up new avenues of research. How might other nonhuman primates structure their vocalizations? Could similar recursive structures be found in bonobo or gorilla calls, given enough data? And how do these findings intersect with the study of music, rhythm, and even the neural timing of conversation?

The forest, it turns out, may hold more than echoes. It may also carry blueprints.

Further Reading and Related Research

De Gregorio, C., Lameira, A. R., & Gamba, M. (2025). Third-order self-embedded vocal motifs in wild orangutans. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.15171

Lameira, A. R., & Hardus, M. E. (2017). Orangutan vocal behavior and the evolution of speech. In D. W. Gray, M. J. Schlesinger, & M. M. C. Tomasello (Eds.), Primate Communication (pp. 73–92). Cambridge University Press.

Gamba, M., et al. (2021). Temporal and rhythmic structure of orangutan vocal behavior: Implications for the origins of musicality and language. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 376(1835), 20200394. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0394

Ravignani, A., Honing, H., & Kotz, S. A. (2017). The evolution of rhythm cognition: Timing in music and speech. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 303. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00303

Chiara De Gregorio et al, Third‐order self‐embedded vocal motifs in wild orangutans, and the selective evolution of recursion, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1111/nyas.15373